Reza Shahriar Rahman

The River That Killed My Grandfather

The historical relationship between Bangladesh and India is not merely a relationship between two countries; it is a relationship of sharing resources, culture and language, feelings of kinship, land, mountains, forests, and rivers. The concept of borders after the partition in 1947 and the birth of Bangladesh as a separate nation from Pakistan in 1971 has changed the socio-economic and political realities of these two nations. Though India played a big supporting role during the war; the post-war relationship has been largely determined by politics, national interest, politics of religious minorities, and resource sharing. India has become the big brother and has been directing forcible zeal to swallow Bangladesh through her hegemonic policies for the last 43 years. India has never given Bangladesh an equitable amount of water when it comes to sharing the 54 transboundary rivers that flow from India to Bangladesh. The biggest dispute between these two countries is over two major rivers, Padma and Teesta. The whole of northern Bangladesh and the Bangladeshi part of the ‘Ganges Delta’ suffer from scarcity of water during the dry season (winter and summer) and gets flooded during monsoon. About one-third of the total population of Bangladesh (approximately 50 million people) faces two extreme ends of the water crisis in this region due to human intervention in the water flow of Padma.

Ganges, the major transboundary river originating in India, takes the name “Padma” when it flows through Bangladesh. The 2,525 km Ganges River originates in the western Himalayas in the Indian state of Uttarakhand and flows south and east through India into Bangladesh, where it empties into the Bay of Bengal. Ganges is the third largest river by discharge. It created the largest delta in the world, where the largest mangrove forest Sundarbans grew.

India has made a barrage on the Ganges called Farakka Barrage (operations began on April 21, 1975), located in the Indian state of West Bengal. The purpose of the barrage is to divert 40,000 cusecs of water from the Ganges to the Hooghly River for flushing out the Kolkata harbor and irrigation.

Bangladesh and India have had many debates on how the Farakka Barrage cuts off Bangladesh's water supply and how to share the water. After the completion of the barrage at the end of the summer of 1975, both countries agreed on running it with specified discharges during the remaining period of the dry season of 1975. But after the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on 15 August 1975, relations between the two countries became greatly strained and India continued to withdraw water even after the agreed period. The agreed period of operation for 21 days of Farakka Barrage has never stopped since then. The diversions led to a crisis in Bangladesh in the dry season of 1976. In 1977, Bangladesh lodged a formal protest against India with the General Assembly of The United Nations. Talks between the two countries reached no consensus.

Twenty years later, in 1996, a 30-year agreement was signed. It did not contain any guarantee clause for minimum amounts of water to be supplied to Bangladesh, nor were future hydrological parameters taken into account. As a result, the agreement failed to provide the expected result. Negotiations continue to till today.

In Bangladesh, the diversion has raised salinity levels, contaminated fisheries, loss of fish species, hindered navigation, drying of Padma's distributaries, and posed a threat to water quality and public health. There’s no sign of water for miles after miles in the summer in some places because the barrage holds up 50% of the total flow to have more water in the Indian part of the river. In the monsoon to avoid the flood, India opens up the barrage, and the flood, the monstrous flow washes away everything on its way. But during summer the riverbeds get filled and sand grabbers steal tons and tons of sand. Thus in the monsoon, the flood flows unnaturally. 50% of the Sub Rivers that came out of this river are dead. And the mighty flow of Padma is no more than a big canal now.

There was a time when the mighty Padma had its pride, its wrath, and its love. There were times in the monsoons that this river had no end. I grew up by the banks of Padma, I learned to swim in this river. My grandfather had a beautiful house on its bank. On a monsoon in 1996, the Padma suddenly gobbled that house. My grandfather couldn’t forget the sound of the splashes of water washing off the house away. He had a heart attack after it and eventually, he left the world silently. The River Padma took away my grandfather and the only memory of him, the house.

This is the story of millions of people living by the bank of Padma. They have no other option but to shift their houses to higher lands. And those who had no other land became homeless. Also, the whole of northern Bangladesh and the Bangladeshi part of the ‘Ganges Delta’ suffers from the scarcity of water in Padma. In the summer, thousands of hectares of land dries up and the poor farmers cry for the water in the river to irrigate the land.

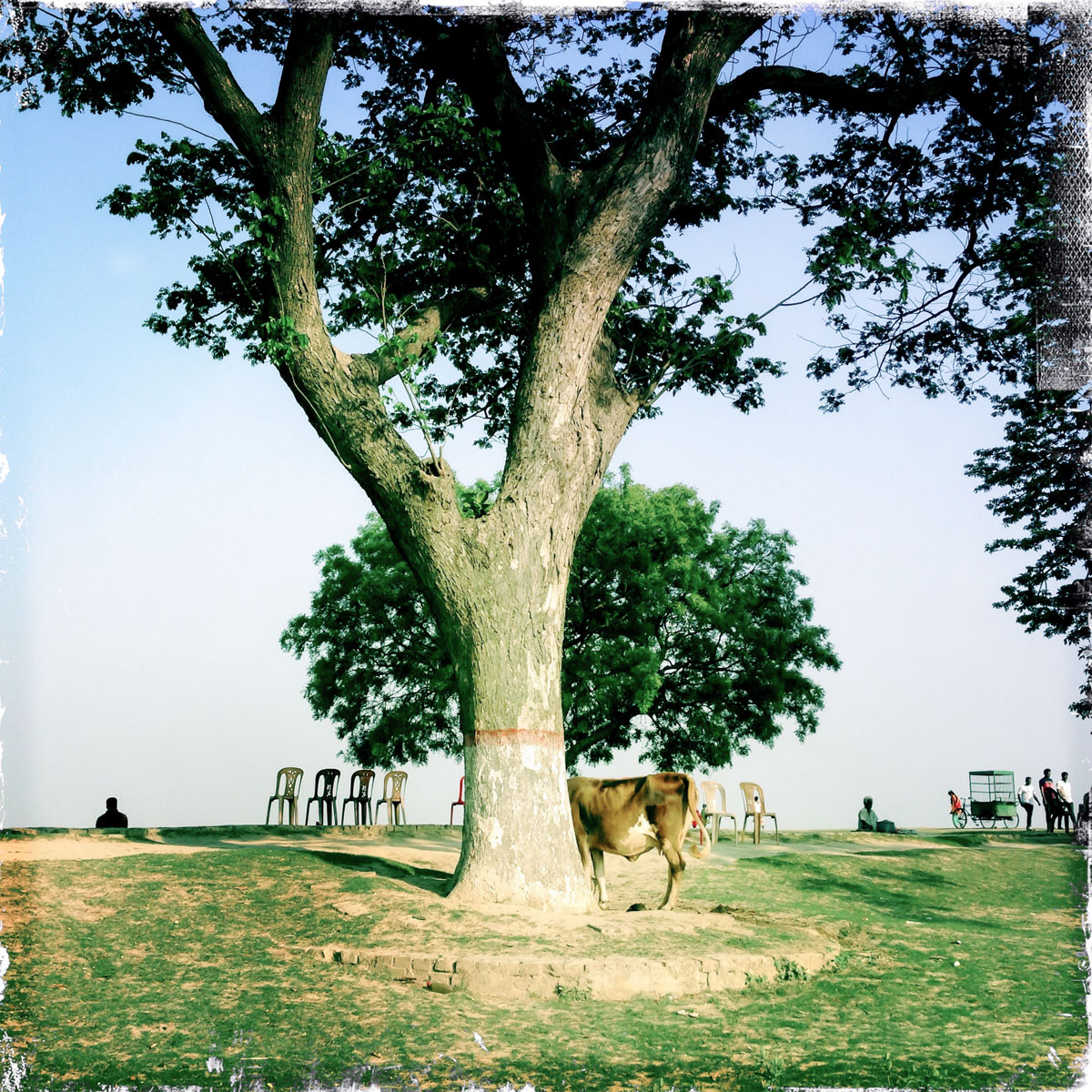

Due to the dying river, the life and the landscape changed greatly by the banks of Padma. I have been traveling along the banks of Padma, 120 kilometers from the north to the south, where Padma becomes Meghna and most of the ‘Ganges Delta’ inside Bangladesh to observe the life and landscape and their shifts. I would be traveling and photographing for the next few years in pursuit of the story of “The River That Killed My Grandfather”. This story is of the sufferings and changes in the lives of more than 50 million people and the landscape of about 75,000 square kilometers in the Bangladeshi part of the ‘Ganges Delta’. This is the everlasting aftermath of the “Love story of Bangladesh and India”.